Taner Erdogan is a force within the martial arts. The 45-year-old practices a distilled approach to kung fu at his school, where its lessons reach far beyond combat and apply to work, relationships and life. Here, he tells us why.

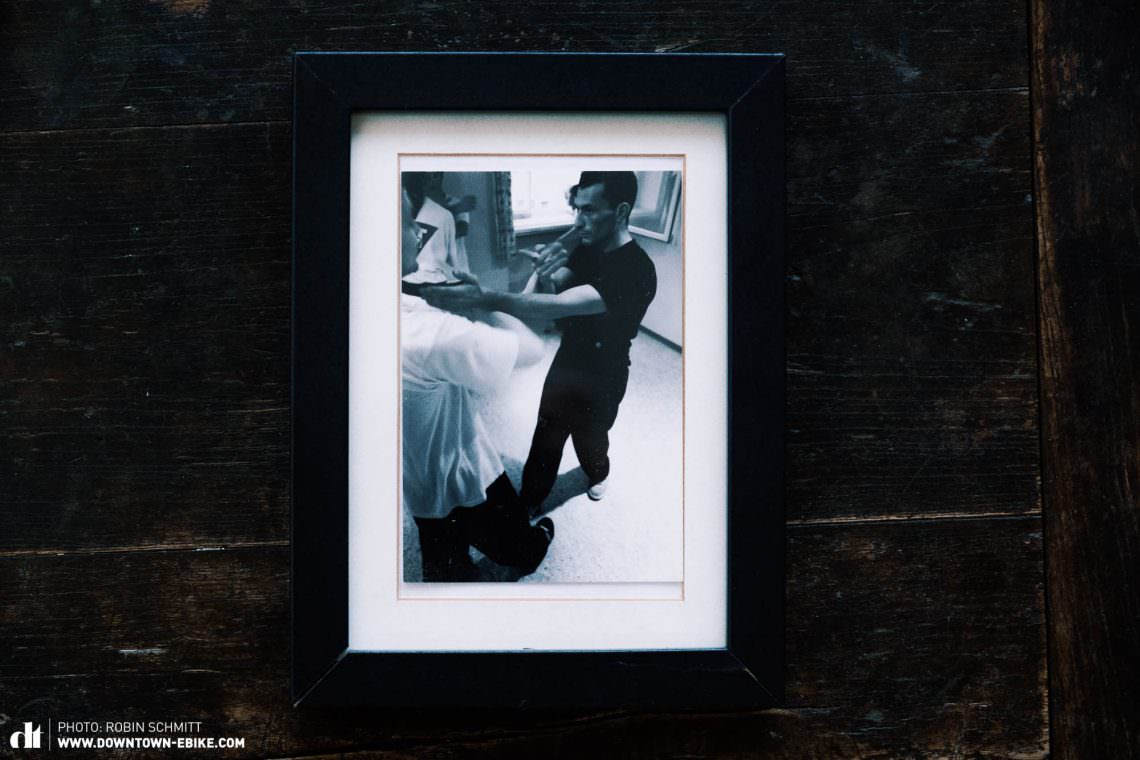

The Cantonese word Shifu is the polite title for a figure of authority – a ‘master‘ or ‘teacher’ in martial arts. The first time you meet Shifu Taner Erdogan, the term seems apt. In conversation, his eyes sparkle and he holds himself in a way that commands respect. With his students, he has a gentle, attentive manner. An avid practitioner of kung fu for 26 years, the Turkish-born German has trained under many different masters, learning the art and how to question it before eventually establishing his own system. It’s not just about learning the art but identifying what actually works, giving up superficial tricks in favour of the things that are truly effective – an approach that makes him his own worst enemy.

But Shifu Taner isn’t only into martial arts – he is also a cyclist. In the summer, his Porsche stays in the garage while he goes by bike to his kung fu school.

After we went cycling with him (which lasted two hours), tried fighting (and lasted no more than two seconds), we decided to concentrate on what we do best: an interview. Shifu Taner initiated us into the ways of his kung fu system, not just teaching us how to be better fighters but about better ways of dealing with stress and pressure in our lives, as well as turning your gaze inwards.

Taner, what is kung fu?

Kung fu is a term used for the martial arts, but it encompasses many different styles. The Wing Chun Kung Fu, which I practice, is about achieving the most with what you’ve got. Always presume that you are at a disadvantage, that your opponent is bigger, stronger, and heavier than you are. My goal is still to overcome the aggressor, but with as little effort as possible. Technique over strength, that’s the main combat element.

This requires you to use your body in the most efficient way you can. Not through building muscle, bulking up, or stretching beforehand. Exactly as you are – we maximise your effectiveness in the moment. You could argue there’s a hint of laziness to it [laughs]. Naturally, the more you train kung fu, the more it will change your physique, your awareness of your body and your abilities, but it’s still about what you have in the here and now. You can’t stop a fight and say, “Wait a moment, can we come back in 6 months when I’ve trained more?”

What is special about kung fu?

Kung fu changes something within you. Not just an ability to defend yourself or learn techniques off by heart. It brings about an enormous sense of inner peace, helping you to know yourself better. The self-confidence instilled in you by practising kung fu means you can keep your cool, emotionally and mentally, whatever situation you’re in.

My journey through kung fu was like a jigsaw puzzle, I was trying to complete a picture. The kung fu systems that I was encountering as a student appeared to have holes in them, to which no one could really give me a decent answer. I started searching. Was there someone out there doing it better? I explored as many styles and martial arts concepts as I could. Some were doing things better in a certain sense, others less so. I kept finding pieces of the puzzle. Eventually, I understood that it can only work this way, if only for anatomical and physical reasons.

The system of kung fu is one of the most selfish, egocentric systems to exist. It’s all about you. Not the guy standing opposite you that wants to hit you. You have to take control of your body and mind in order to respond in a situation. Most people lose a fight before they’ve even entered any sort of physical combat, providing, of course, the opponent has an idea of what they are doing. At the beginning, the most important element is to know yourself and know what you are capable of. What can your arms do? Your legs? How do I transfer power? Many people have a warped view of this. “The more power I exert, the more it’ll hurt them.” That’s wrong. Power is predominately transferred through relaxation and speed. If I accelerate something that’s relaxed, or static, the power transfer is more effective. If I hurl something tense and contracted, the result is inertia and less power. I have to learn the meaning of ‘relaxed’. Getting to know your own body is crucial. Which muscles are important? Which should be contracted and which need to stay loose? Which ones are supporting me, which aren’t?

We do this every day – when we ride our bikes as well. It wouldn’t make sense to grip the bars fiercely and tense your body when you are about to drop into a trail or ride up a kerb. You basically act as a block to yourself. If you want to properly utilise your physical and anatomical advantages, you need flexibility, momentum and the right balance between relaxation and tension to make sure your bike takes off, your body works as suspension and that you don’t physically bear the brunt of the impact. This is how kung fu works too. Over time you get to know your body and what it is capable of. I might show some basic moves with astonishing effects to a guy on the street, and they’ll look at me flabbergasted because they can’t comprehend how much power you can transfer when your body is relaxed.

How do you go from being a follower to a leader? Do you have to question the masters in order to find your own way?

At the beginning, you have to abide by what your master says. Listening to teachers is so important, even if you think you could do it better. It’s about obtaining knowledge and ability, not about egos. Take Muhammad Ali – he could have knocked out his teacher in 2 seconds, but that’s not the point. The teacher’s role is to turn you into a champion, which is exactly what Ali’s teacher did.

Listen when you meet new people, take a step back and don’t presume you know everything as you will neither listen nor learn. People forget this. In martial arts people lose their way early on because they want to impress the master or their peers, forgetting that the only thing that matters is learning and improving: to progress. I’ve had the honour of having some incredible masters that I will always appreciate.

You have no choice but to copy the teacher at the beginning, but always keep in mind that you are an individual. You control your body and mind. This copying lets you eventually crystallise who you are. Then, you’ll start, as Bruce Lee so beautifully said, expressing yourself through the art. Learning a martial art involves first learning a form before you step away and form yourself.

So many of us always want to give 100 %, whatever we do. We get stuck in the details and forget to look at things as a whole – how can we find the essence?

Over time you’ll learn what your body responds to. Where and when it feels good. A few years ago I reached the point where I was ready to throw away everything I’d learned over the decades because I realised it was actually only five or six movements that I needed. Then, eventually, even these five or six stances weren’t important. If you are only able to effectively deploy 1% of your strikes but you learn 100% of them permanently, that’s inefficient. I distil that down so that the 1% of moves that remain are 100% consistent for me. That’s the idea behind my system. Very, very few moves, but all of these few moves that you use in combat are at 100%. We have two arms, so does your opponent. You can only land a strike with your arms parallel, crossed, or moving in and out of each other. Four moves, four techniques. In training, you don’t even do these actively, just passively. No more, no less. If you encounter someone with four arms, you’ve got other issues. Bruce Lee once said, “I fear not the man who has practised 10,000 kicks, but I fear the man who has practised one kick 10,000 times.” We need to first acknowledge why we need a move before we simply drown in a flood of techniques.

What are the biggest challenges in combat?

The biggest fight is always against our own self. Techniques only work when the mind cooperates with the body. When you can control yourself and your movements, you can decide how you’ll react. Will you get angry or not? Do you become aggressive or do you keep your cool? You force your mind to stop, to either carry out a movement at a certain point or not. Greed and ego are removed from the equation. It enables you to exercise extreme emotional control. Without that, you act rashly. With some luck this might go well, but not always. That doesn’t just apply to combat but also to work or relationships – all situations that might need resolving from time to time.

On the occasions when you’re fired up, it usually goes wrong. The smartest move is to see what the situation needs and what your capabilities are. At that moment, you’re best off doing what you know you can do. Don’t be influenced by anyone else. Make your own decision. Don’t chase your tail. Being patient is very important. The beautiful thing in kung fu is that you can’t really brush aside a wrong move – it feels more like a smack in the face. [laughs].

Space, time and energy are extremely important. Mastering these factors and learning the right distance to keep from things puts you in a position of extreme self-confidence and strength. Your calmness and control make it difficult for anyone to try to assert control over you. It takes practice, but it builds you up.

The important thing is the belief in yourself. Believing in your movements and the system. This is what it depends on. It won’t work if you let in any self-doubt. I try to convey this to my Kung Fu Pandas, my kids’ groups, in everything they do. They need to develop trust in their abilities and their bodies. First, they have to know their body and what it is capable of – the same as adults, but a bit different. The phrase, “I can’t do that,” is not in my lexicon. It does not exist. We try, we train and we will do it one day. Maybe not today, but we strive for it. I think it’s incredibly important to teach children that they are not weak simply because they are smaller or heavier than their friends. It pains me when they are picked on. I want them to develop into strong characters. I feel the same about adults. Capabilities are never set in stone and we can work on them and develop at every age. Many people give up or perhaps don’t even attempt to learn something, but it is such a shame to see potential go to waste. I took in new students last year and many of them were 50+, which was great. Martial arts aren’t just for young people. Asian kung fu masters practise until they are well into their eighties. And they’d probably still knock you out.

What about the occasions when you know theoretically how you should react in a situation, but you’re swept away by stress. Isn’t that where most of us come apart?

One of our goals with kung fu is learning to exist with pressure, haste and stress. When someone tries to stress you in kung fu, they’re trying to de-centre you and put you off guard. You have to keep centred, stay relaxed, and not rise to the pressure the opponent puts you under. When two sources of power come head-to-head, the one that’s most powerful in that moment wins. So take their strength rather than giving yours away. This is how you permanently control your centre and have the power to act. No matter how quickly it happens, others will see an extreme sense of sovereignty in your actions. The stress arises from an uncontrolled reaction.

We want to constantly move forward in kung fu, but it doesn’t always happen. At times an opponent might exert such pressure or force that you go backwards to protect your centre and keep control. It’s like a glass of water that’s already full but your opponent is trying to pour more. You pull the glass away and drink a gulp before it overflows, giving you more capacity for new water. Otherwise, it will spill, you lose control, the glass overflows and you have a mess to clear up.

If you do not have a hold on yourself, everyone will stress you. All it takes is someone in a bad mood. But it isn’t to do with him unleashing stress; it’s you allowing your own stress to take over.

When someone exerts pressure on you, either evade it or capture it and ask yourself, how can I transform this into something positive? The energetic potential of pressure and stress can move you. How can I use this momentum positively? Or in a calming way? Such a transformation requires the ability to see the positives in everything.

So, you’re saying to keep cool, stay positive and it’ll all work out?

Before I started my own company I worked for a large German corporation. My boss had real difficulty with my inner peace, and once said to me, “It makes me so sick that you sit here so peacefully even though you know exactly what is at stake.” He never understood that everything worked and I always delivered. In my opinion, it frustrated him so much because he was frustrated and overwhelmed by stress and he wanted me to go through the same.

In certain situations, you may have to exhibit some signs of stress too

It can lead to similar problems in a relationship. I’ve since learned that you might have to simulate stress around certain people. My boss isn’t the only person to struggle to deal with the fact that I keep my composure. My behaviour back then might actually have looked a little different if the current me worked with him these days… I’d make an effort to reflect some of the stress he so badly wanted me to express. It might make him happy.

In certain situations, you may have to exhibit some signs of stress too. The biggest difference here is that you’re acutely aware of this, whereas others are at the mercy of it. You stay in emotional control, deciding how to react. That’s a very different and extremely controlled approach to stress.

There are always three options: when someone looks you right in the face and says, “You absolute dickhead,” you could either smack them in the heat of the moment, or you could smack them with control. Or do nothing [laughs]. You can act either way, but the knee-jerk reaction makes you a puppet. Your opponent pulls a string, you raise your arm. Or he pulls the string and you consider your options – do you really want to raise your arm?

Some years ago I was at a business dinner at a Mexican restaurant in Cologne. My steak had just arrived when a waiter passed behind my chair, nudged my head with his elbow and tipped his entire jug of salsa over the back of my shirt. It happened at exactly the same time I was cutting my steak, which I continued to do, before putting a piece in my mouth and enjoying every morsel. My colleague looked at me in awe and said, “Taner, the waiter just poured salsa all over your shirt!” I said I was aware of that, but what was I supposed to do in such a moment? I could jump up in outrage at the waiter’s clumsiness, but what would that achieve? Finally, I put my knife and fork down and stood up as the waiter arrived with some dishcloths. I washed myself as best I could in the bathroom before rejoining the table. These are the sort of moments you realise how important the idea of control is. Will it help the situation if you lose your shit? No. Nothing does. Act with awareness and control. The waiter had not done it on purpose, so why should I shout at him? He made a fool of himself, and perhaps, if his boss is enough of an idiot, he may even have lost his job over it. The fact that I stayed composed perplexed the rest of my table. And you know what, it isn’t easy to do that when you have salsa running down your neck and you’re cutting a hunk of well-cooked meat. Fortunately, I managed.

As I said earlier, if you cannot control your body, there’s little chance of controlling your mind. If it acts impulsively, your mind immediately springs into defence mode and you have lost. You put yourself in a position you don’t want to be in. Your opponent takes control, exercising their influence over you. This should not happen – not in combat, nor daily life. Think of the puppet. It’s a never-ending learning process, but you have the opportunity in every situation to learn how to act. That is a beautiful thought.

Eventually, everything you do in kung fu will be intuitive. After so many repetitions, your arms will know instinctively what to do. You trust them, you let them do it. You step back and take your position as an observer, acutely aware of when it is too late to act, and whether an action or a reaction will help. If something has already happened that cannot be retracted, it’s up to you to resolve the situation. I firmly believe that the best thing to do is to stay calm.

Thoughts race through your head as the salsa runs down your back and you may curse the moment, but the steak is still warm and you’ve just cut it ready for the first mouthful. Instead of letting your evening be ruined, enjoy the freshly cooked steak. We are so susceptible to other people’s influence when we are not aware of our own actions, especially when it comes to irrelevant things. Think about how tensions flare up so much over parking spaces in car parks. It never ceases to amaze me. Now I’m not advocating giving up your space every time but at least to act in a measured way. While we’re striving to take control and be thoughtful, we should not overlook the fact that we are humans. We have good days and bad days. Some days you react fitfully, other days you let it pass by. It happens. We aren’t robots. But what’s key is acknowledging the situation, regardless of whether you reacted in the way that you wanted to.

What makes a master?

I don’t believe there is one single master. We are always learning. You are a student throughout your whole life, permanently learning and developing. That, to me, is mastering. You reach a state of inertia as soon as you say, “I’m a master; I can do that.” With that frame of mind, regression and being overtaken by others who are still open to learning is the inevitable result. True mastership is knowing what you’ve learned while still listening to others and learning even from those who may consider themselves below you, as they could hold information that you don’t yet know. Masters are open to progress, open to development and fulfilment at all times.

We could have asked this question right at the start, but it fits nicely here. What does kung fu actually mean?

Translated, kung fu means to achieve much with little effort, or to be able to dispatch hard tasks with ease. You’re able to complete things even though they are hard. It’s an ability and skill, that you have learnt and trained through hard work. To the observer, it looks as though you simply stretch out your arm and your opponent flies three metres across the ground. That’s kung fu for me. Nothing else comes close. A master chef travels, tastes other cuisines and watches what’s happening in other countries – they visit kitchens that haven’t even made a name for themselves yet. That’s a sort of art. The continual pursuit of learning. You see the same with children. We learn a lot from them by listening. They might challenge you, but what’s really stupid is presuming that your age makes you immune to learning. You put yourself in a state of inertia. Water, or a river, is a good metaphor for kung fu. It doesn’t think, has no future or no past, but is permanently there, flowing onwards in the easiest direction. There’s no chance of it stopping and staying, “Well I could go that way, but let’s take a left over the rock and up the embankment for another direction.” No, the river looks for the path of least resistance. But put in a confined space and under pressure, it’ll force its way past you. Whatever the water does, one thing is for certain: it flows onwards and won’t be stopped. When I tell this to my children, they always ask what happens when it freezes. Well, at that moment, it becomes ice and not water. [laughs] Kung fu is the same. It’s about following the path of least resistance but teaching you to pierce through granite when needed. When that’s not needed, you’re gentle. You follow your intuition and intention to keep on moving forward. Water isn’t likely to stop and say, “Ok, enough for today.” A large rock in its way won’t send it into a spiral of stress. It slams into it and slips away in the easiest direction. It won’t pain itself to move the boulder, but it might happen, almost as if by itself. That isn’t the water’s primary intention. Its primary intention is simply to move forward, no matter what stands in its way.

Dear Taner, thank you for the interview!

To find out more about Taner Erdogan and his approach to kung fu, or if you fancy some Kung Fu training, visit kungfuleonberg.de

Interview & Photo: Robin Schmitt