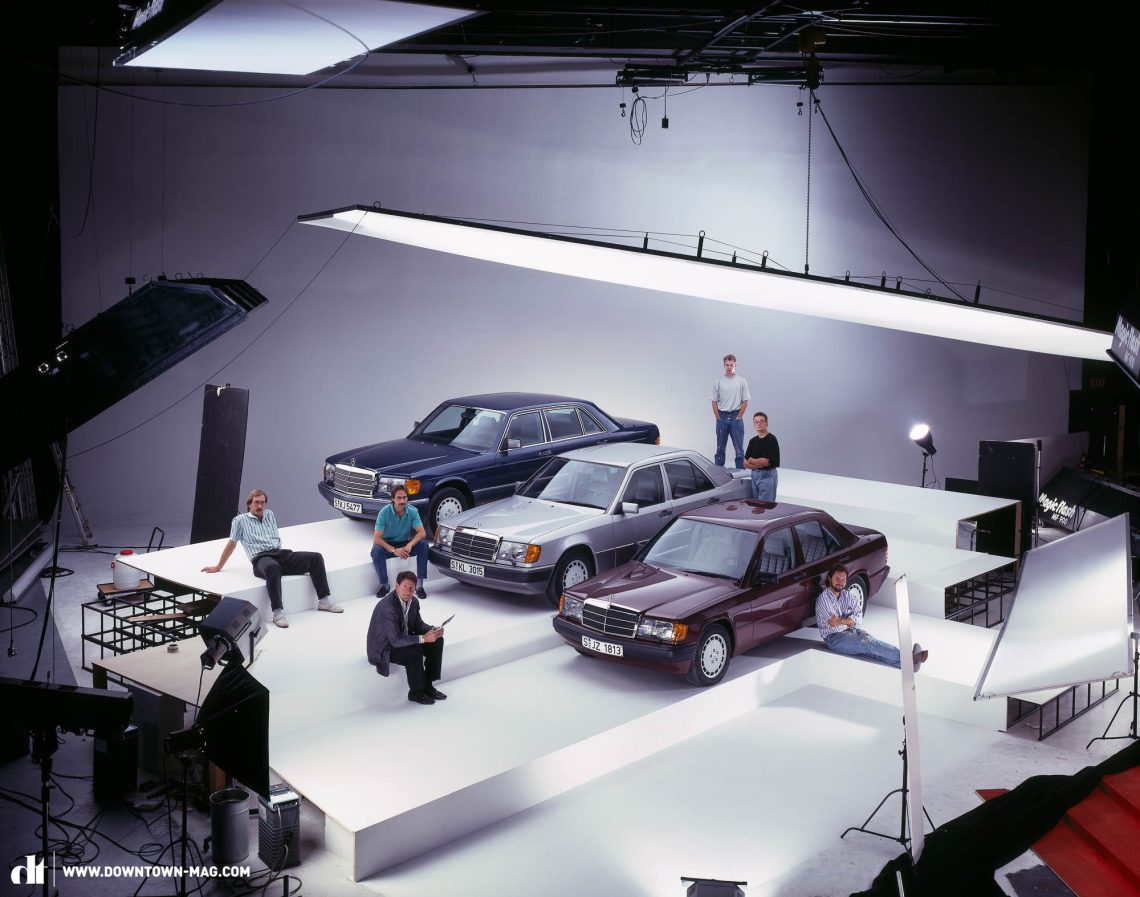

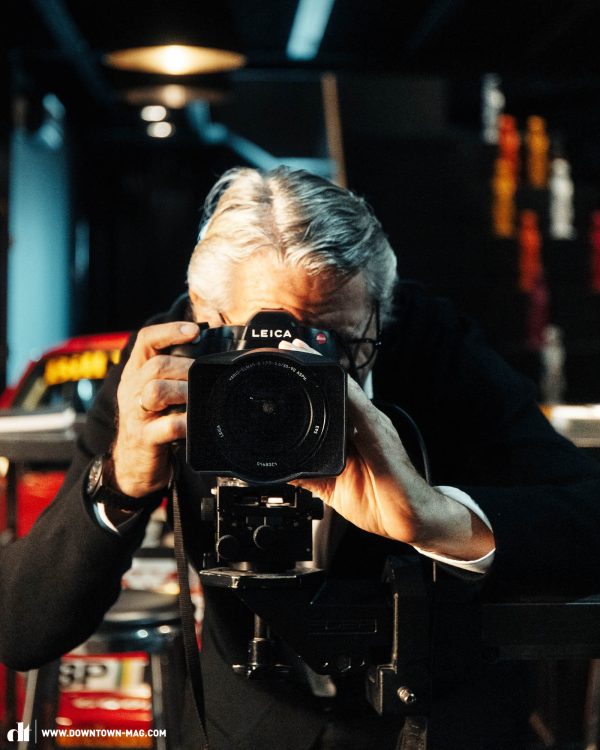

Hardly anyone has accompanied the development of the automotive industry more closely than René Staud. He’s still regarded as the star photographer of the automobile world, the Peter Lindbergh of cars, and has had every important car in front of his lens over the past 50 years. We visited him at Staud Studios to talk about automobile design, dying icons, dominant behaviour and the future of mobility.

Dear René, with over 50 years of automotive photography, you’ve accompanied automobile development like hardly anyone else in the world. From your point of view, what’s changed the most over the last decades?

I’ve been following the development of the automotive industry since the 1960s, especially from a visual aspect through the lens of the camera. It was generally a completely different world back then: cars were in short supply in Germany and the demand was so high that they didn’t need to be marketed. Not so in the USA, where the market was already saturated, which meant that they were far ahead of us in terms of automobile advertising and photography. I photographed my first car at the age of 15, at which time car advertisements were still drawn by hand. There were hardly any marketing departments back then and nobody had thought of target groups. If you photographed cars, you did so in nature, and you rationally depicted their practical benefits. You usually didn’t even have brochures at the time, so the communication was still very rudimentary, and nobody thought about how desirable a car could be – and how it could be represented accordingly!

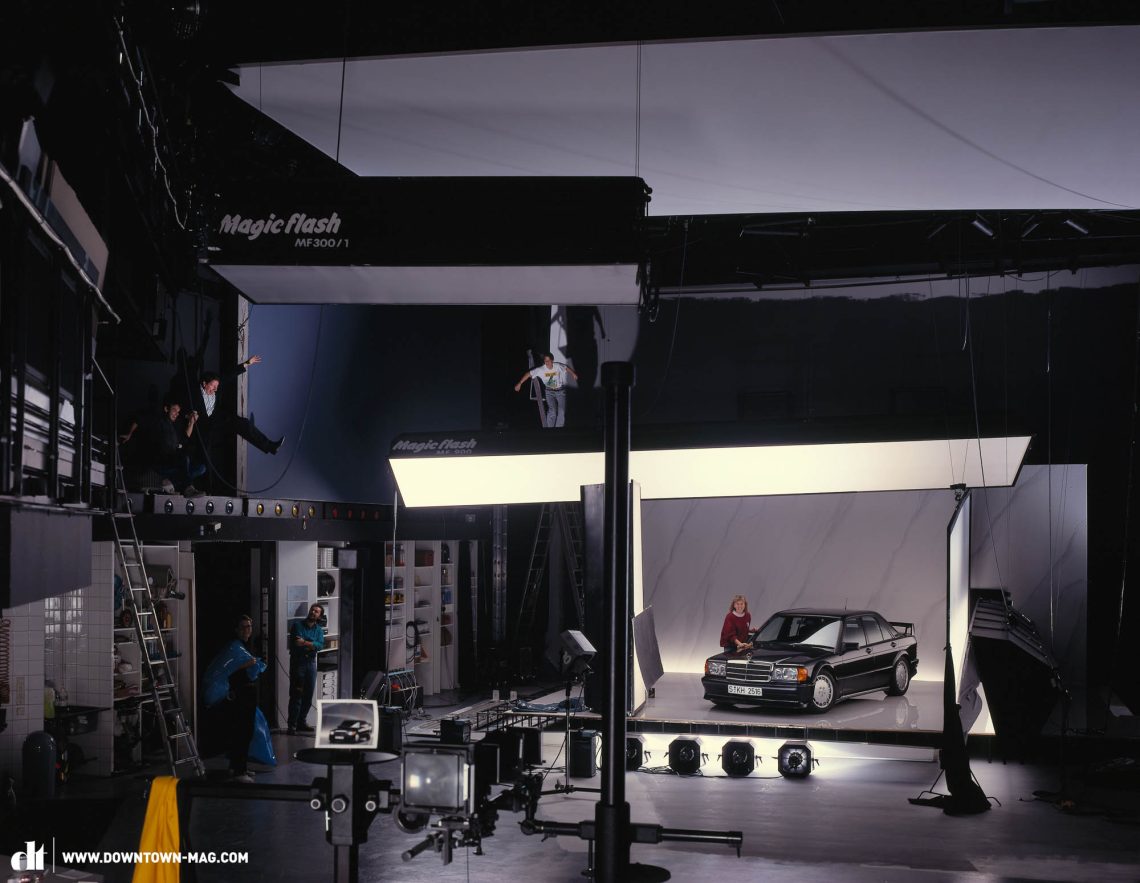

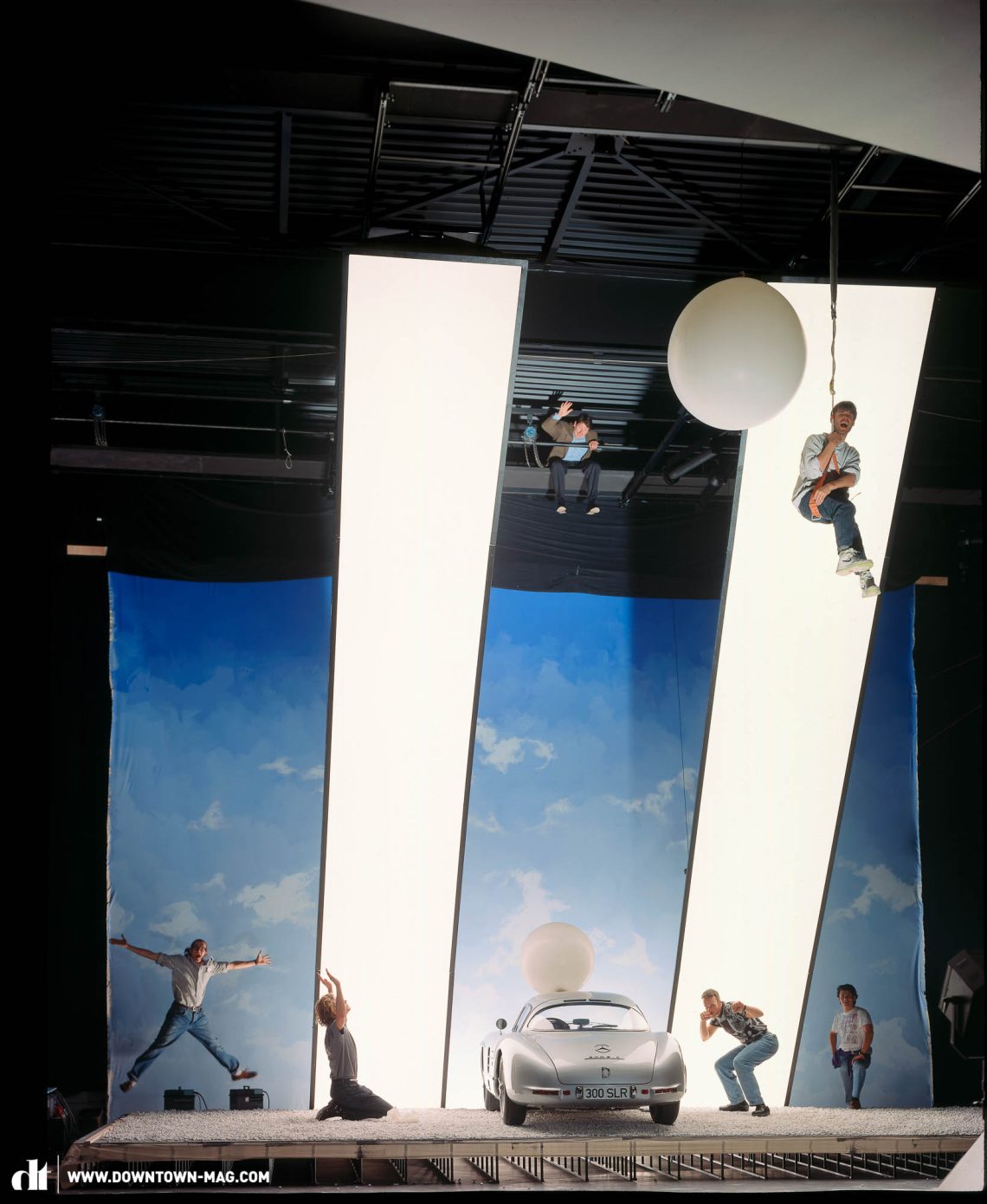

It was only at the end of the 1960s that automotive photography started developing, which also changed the representation of cars. For the first time, cars got photographed like other industrial products, elegantly and cleanly staged. And so began the era of studio photography. I realised early on that cars and design objects should be staged deliberately, like people in nude photography. The less lighting you use, the more you can emphasise certain features or leave open to interpretation. Incidentally, this also reflects the marketing process of cars at the time. Back then, the concepts originated from the design and not from a marketing perspective. That’s all changed completely: to market a car today, marketing departments run huge target group analyses and develop communication strategies. Before, a small team could decide on new products or designs, whereas corporations now have huge armies with infinite coordination processes. Of course, this is also due to the fact that automobile manufacturers want to secure themselves because every new model requires a huge investment.

Automobile photography has changed dramatically too. Today, you can’t do anything without CGI, which is short for Computer Generated Imagery. Twenty years ago, Staud Studios were the first to invest in this technology, which was still quite new at the time. While many other photo studios had to close, we invested in new technologies, which even allowed us to grow significantly. Today, the bulk of our business is in CGI. With CGI we can create and animate images using 3D computer graphics. This technology originated in the film industry to create special effects and has become an indispensable part of marketing.

In the past, cars represented freedom, glamour and the future. Today, many cars get criticised – they clearly seem to have lost a lot of their original appeal. Can you tell us why you think that’s happened?

This is an important question which you probably need to consider from several different perspectives. We’re talking about a kind of perception, which changes from one person and culture to the next. A lot of it gets controlled externally, then comes the design, and, ultimately, we get taught what we should feel, determining whether we love or hate something.

Let’s start with the external control: politicians prescribe a certain way of life and control it through climate policies that often categorise things – in our case cars – into good and evil. Today, combustion engines, especially diesel, are categorised as evil in climate discussions. Meanwhile, a few years ago, diesel was perceived as very environmentally friendly, and in advertising, the trees almost smiled at the cars. But, today, politics demonises diesel engines. Why? Because of the falsification of the emissions values. The diesel scandal has damaged its credibility, which has dramatically influenced people’s perceptions. That’s how good became evil. It was a huge mistake that affects diesel’s image to this day. And it continues to undermine the facts, even though people actually know that this isn’t justified. And that brings us back to advertising: advertising can communicate things, but it can never correct misperceptions because advertising doesn’t get taken seriously. Unlike journalism, advertising isn’t credible. This is the dilemma facing advertisers and photographers: photos cannot correct a bad image.

Another reason for the decreased popularity of cars is the design. The key word here is globalisation. These days, cars don’t get designed by a single designer but by whole teams of designers. There’s no coherent theme for the design as a whole because it isn’t one designer’s vision. Instead, you have one design team tasked with designing the grille while another team is responsible for the headlights and another team still designs the door handles. It lacks character.

Of course, it’s also due to the current zeitgeist. Attitudes and tastes change. And tastes also have to be acquired. Take the Porsche 911 drama, for example, it garnered a lot of critique, even from the zeitgeist of the ’50s. It might have been technically superior to the 356, but it had a tough start nonetheless. It’s the same with people, you can meet someone where the chemistry just isn’t right. You don’t like the way they look and the way they walk… It’s only when you get to know them that you begin to overlook all these things and see the good. Sometimes, you just have to get to know someone to learn to appreciate them. Ultimately, the 911 won us over because it’s so much fun to drive. And its design now makes it an iconic classic.

After three to four years, a car is considered old, but after 15 years it’s back to being ok, as it starts getting into young-timer territory, in which case being 15 years old is a statement.

That said, the zeitgeist has taken a very strange turn. Design has become very angry: aggressive grilles and lights that look angry, big hulking SUVs and hard, straight lines have become the norm, not the exception. Added to that is the colour palette: instead of chrome, everything is black, apparently making cars cooler, though it also makes them seem a lot less friendly.

Why do you think car design has become so much more aggressive? What does that tell us about people and society?

A part of it has to do with the behaviour of dominance on the roads, but it’s also due to the desire to feel safe. In a classic old-timer, you feel small and vulnerable, and it’s not the kind of car you want to drive on the highway. On the opposite side of that, you’ve got your SUVs. You feel invincible driving one of those. As such, it makes a lot of sense rationally, that SUVs have become the classic family vehicle for those who can afford them. In a big car, you just feel a lot safer and more confident. And the bigger and stronger you feel, the better you feel. Moreover, there’s a thin line between self-confidence and aggression.

Automobile traffic is generally quite aggressive, and, ironically, you feel that the most when you’re driving an aggressive car. In that case, it’s all about the pecking order and seeing who’s bigger and stronger. You’re in a constant battle. There’s been a clear uptick in this sort of behaviour over the last few years. People have become sensitive and being overtly aggressive makes them feel safe. The same applies to the online world, by the way.

Interestingly, it can work the other way around too. When you’re driving a special car, like an old-timer, the reactions you get are completely different. Suddenly, people are no longer in that much of a rush, they’re happy to see an old-timer and they’d never think of pushing you off the road. You could say classic cars bring out a kind of gentleness in other drivers, just like puppies do in older dogs. I would like to see the automobile industry or rather future automobile designs become a little less aggressive.

On the topic of anthropomorphising, Volkswagen say their new ID.Buzz “instantly creates positive vibes with its characteristic smile.” What makes a car likeable and what trends do you see in the design language of cars?

That brings us to a very important aspect: the car’s face. The grille and the headlights make a face with the grille being the mouth, which, depending on the design, can smile or even bare its teeth. The lights are the eyes. The rounder, the more likeable it is since it makes it look childlike. A downwards sloping hood like you have on the VW Beetle also makes it likeable.

However, friendly faces like that of the Beetle are becoming increasingly scarce these days. Nowadays, a lot of cars have similar headlights, which is due to standardisation since you often have the same partners and suppliers. Increasingly complex technology is also becoming more prevalent, which further determines design and results in a lot of parts, including headlights, becoming interchangeable. I often find that I can no longer discern one car make or model from another by looking at the tail- or headlights of cars at night.

In general, there’s no longer any clear design language and the manufacturers are under pressure to keep producing something new, which occasionally results in quite the nonsense. We even saw several faux pas over the generations of the Mercedes SL, whereas Porsche have done a great job of finding their way back to their original aesthetics and lines. And you shouldn’t forget that some brands like VW must produce cars that appeal to the whole world. In other words, they’re not targeting just one market. Their models are made to be global, which results in cars without character. You just can’t design cars with personality that way. In the worst cases, it’s like Frankenstein’s laboratory.

Is there still such a thing as an automobile icon?

For me, there are just 6 icons in the world of automobiles: the Porsche 911, the VW Beetle, the Citroën 2CV, the Jaguar E-Type, and the Mercedes 300 SL and G-Class. This is simply due to my upbringing and the influences from the outside world, and I’m convinced it’s something that gets passed down to us as babies from our mother’s milk. [laughs]

That’s hardly possible these days. Why? On the one hand, it’s because you’ve got around 30 designers working on one model instead of a single designer realising their vision, as I said before. Additionally, these days we have a kind of model inflation. Mercedes used to have the S-Class and the E-Class, whereas you can hardly see the woods for the trees these days when you see all the different models. I’d guess there are around 20 different AMG models alone and around 60 model variants. It’s even become difficult to categorise certain classes of cars since there are just too many different shapes and variations to make a clear distinction, which makes creating icons even more difficult. Moreover, there’s a constant demand for new models and we’re seeing new generations being presented at an ever-increasing pace so that cars are considered old after just three to four years. If you get a new company car every three to four years, you want it to look new, too! But I ask, does it really have to look new? And why does a face lift so often also come with a new motor? It doesn’t make much sense: after three to four years, a car is considered old, but after 15 years it’s back to being ok, as it starts getting into young-timer territory, in which case being 15 years old is a statement.

Do you think the current old-timer hype is due to the fact that modern automobiles are unable to fulfil certain desires?

Well, you’ve got to ask yourself what this hype is all about. Why do people want to have an old-timer? You have to separate the rational from the emotional buyers. Rational buyers often see old-timers as an investment and speculation. They often don’t have much of a technical understanding of them. And then you get those buyers that want an old-timer for nostalgic reasons. For them, it’s about a fascination with the technical as well as design and cultural aspects. It’s cool to get by on primitive, almost prehistoric technology, without an AC and electric windows. Simply enjoying the ride without any frills – there’s nothing more relaxing.

Regardless of whether it’s an old-timer or a new car: technical perfection isn’t everything. Oldtimers have a lot to do with emotions and character. For example, Lexus probably make the most perfect cars. The problem is, they’re so perfect that you forget you’re driving a car. That’s another thing that kills a brand because it doesn’t make you feel anything and hasn’t got character.

Simply enjoying the ride without any frills – there’s nothing more relaxing.

Today, cars are often just a means to an end, getting you from A to B without any emotional value or personality. These days, functional and affordable cars are available from countless manufacturers around the world – there are many we haven’t even heard of. Two-thirds of the cars in Tokyo are unrecognisable to us as Europeans, but they do the job.

German car manufacturers are beginning to worry about their existence because of this, trying to position themselves in the luxury market where it’s about so much more than just functionally, and the value chain is completely different too. Brands, driving experiences and lifestyles like these are usually priced accordingly, which applies to most aspects of life. When I travel and go to rent a car, I don’t choose the car according to the rental agency’s price categories. Instead, I just ask what they’ve got, and then I choose the car I like.

We’re currently stuck between hybrid, electric, petrol and diesel engines… If you could be president for a day, what’s the first thing you’d change?

I would preach an openness to technology, but I wouldn’t regulate or place fines on anything. No bans, just guidelines! I don’t think general bans are the right way because the truth or the answer to a problem often requires a much more nuanced approach. Many bans just lead to new circumventions of the problem or the exploitation of loopholes. That said, it would make sense to only allow electric cars in certain regions. After all, there are ski regions that you can’t get to by car. It might also make sense to have hybrids in some areas, so that short distances within a specific radius can be driven electrically without needing a second car.

A lot of state measures simply encourage more consumption and don’t do much for the environment. For example, I would get an € 11.000 grant when buying an electric Smart, allowing me to drive the little electric car for 3 years at almost no cost. That’s got nothing to do with sustainability. And then you get rewarded for driving it into the city, so you get rewarded for consumption! I ask: is this really driving a change in mobility or is it merely encouraging more or a just different kind of consumption?

Sustainability and eco certificates on luxury cars are the biggest joke. Those 2 percent of luxury cars that are currently on the market hardly make any difference. What really matters is making mobility environmentally friendly for the masses. You’d first have to place a ban on gas and charcoal grills, they produce more fine dust than a few sports cars. One thing I would ban is two-stroke leaf blowers since they don’t just stink but also cost us a lot of nerves with their high-pitch motors, often going above 110 dB!

Do you think e-mobility is a part of the solution to the climate crisis?

Most regulations are regional and don’t make a big impact globally, except to calm your conscience. If you look at the world as a whole, you’ll realise how old the average car is. As far as I know, Morocco has higher CO2 emissions from its 2 million cars than Germany, which currently has 47 million cars. We’re just demoralising people and giving them grants to replace their old cars. But they’ll buy the latest thing anyway. And every car that gets replaced in Germany continues to drive, just in some other country, because our old cars aren’t actually old. We’re just shifting the problem, not solving it. Moreover, the energy source, electricity, is still produced largely from coal.

How do you feel about autonomous cars?

In a perfect world, they’d make our roads a lot safer. But I don’t believe in that. We’re not there yet. After all, we haven’t even managed to get cell phone reception to every part of Germany. And if you look at the disaster we had recently where no one could buy fuel or go shopping because the entire bank and credit card system failed, I don’t want to imagine what would happen on the roads in a situation like that. If the system controlling autonomous vehicles had to fail, millions of cars would come to a halt. Not to mention what might happen in the five seconds before they eventually stop. What about all the older cars, or old tractors and bicycles etc. – what do we do with those? How would they communicate with the new high-tech cars? I believe we’re missing an important piece of technology that would allow autonomous cars to function and communicate without the internet before we can make that step.

You own quite a few electric vehicles including an e-Smart, ebike, e-lawnmower and even a hybrid. Which of these would you miss the most?

Definitely the ebike. I have an eMTB from Storck and I think it’s just the best thing ever, though it took a long time for me to get excited about the concept. I think ebikes are a fantastic vehicle category on their own. I’d like to see the same thing happen with electric cars, that they become a separate vehicle category instead of a replacement for all diesel engines. I also have trouble with hybrid cars. For example, when I drive my hybrid, I often find myself asking things like: is it on? Is the door closed? Is it in gear or not? Which button do I have to push now? None of it is as cool and intuitive as it used to be. They’ve made too many compromises and too much of it is based on the old concept of a combustion engine.

René, thank you very much for the fascinating interview!

It was a pleasure and fun for me too!

Fore more information visit renestaud.com

Words: Susanne Feddersen, Robin Schmitt Photos: Staud Studios, Noah Benjamin, Volkswagen, Lexus